Madeline Thompson and Beth Kellaway explore the immersive displays and emotive language of Nicosia’s museums.

.

Madeline and Beth are studying Geography at Newcastle University.

Our research during our field trip to Cyprus tackled a big question: “What can museums teach us about different community perspectives in Nicosia?” We zoomed in on three contrasting museums: The Centre for Visual Arts and Research, The Turkish Museum of National Struggle (TMNS), and the Greek Museum of the National Struggle (GMNS). This project was created with the aim of updating the insights from Papadakis’ 1994 study on Nicosia’s museums. We used a mix of auto-photography, semi-structured interviews, and a sixteen-question survey that we, five undergraduate Geography students, completed ourselves. Museums like GMNS are crucial for reinforcing and educating narratives, making them vital institutions in our society.

Of the three, the GMNS stood out for its intense, emotional storytelling about the so-called ‘Cyprus question’ and its take on peace and reconciliation. This museum used emotionally charged words to shape visitors’ perceptions: the British for example were referred to as “torturers” and “interrogators,” while every EOKA fighter was hailed as a “hero” who “died in honour.” EOKA being a Greek Cypriot, nationalist movement that sought to end British colonial rule in Cyprus. This language blends ancient Greek values of civic duty and bravery with Orthodox Christian martyrdom. Turkish Cypriots, on the other hand, were stigmatised as “mobs.” This portrayal likely stems from this community’s support for the British, fuelling ongoing hostilities. The GMNS’s narrative sought to shift blame from the EOKA movement and onto others, something which might not help the peace process.

The final exhibit is particularly striking – a beam with three nooses, surrounded by 108 candle-lit alcoves, each with a photograph of a fallen soldier. This display offers an immersive experience, connecting visitors emotionally with the exhibits, arguably creating an imagined community and subsequent collective memory of the events and traumas.

Alongside such emotive language the GMNS makes use of space to deliver a powerful message. The final exhibit is particularly striking – a beam with three nooses surrounded by 108 candle-lit alcoves, each with a photograph of a fallen soldier. These photos restage past trauma, leaving a lingering impression that Greek Cypriots haven’t forgiven the British. This display offers an immersive experience, connecting visitors emotionally with the exhibits, arguably creating an imagined community and subsequent collective memory of the events and traumas. The museum’s design and objects weave a complex geopolitical narrative that ties visitors to the historical struggles of Greek Cypriots, highlighting their view of the Cyprus division as a historical injustice.

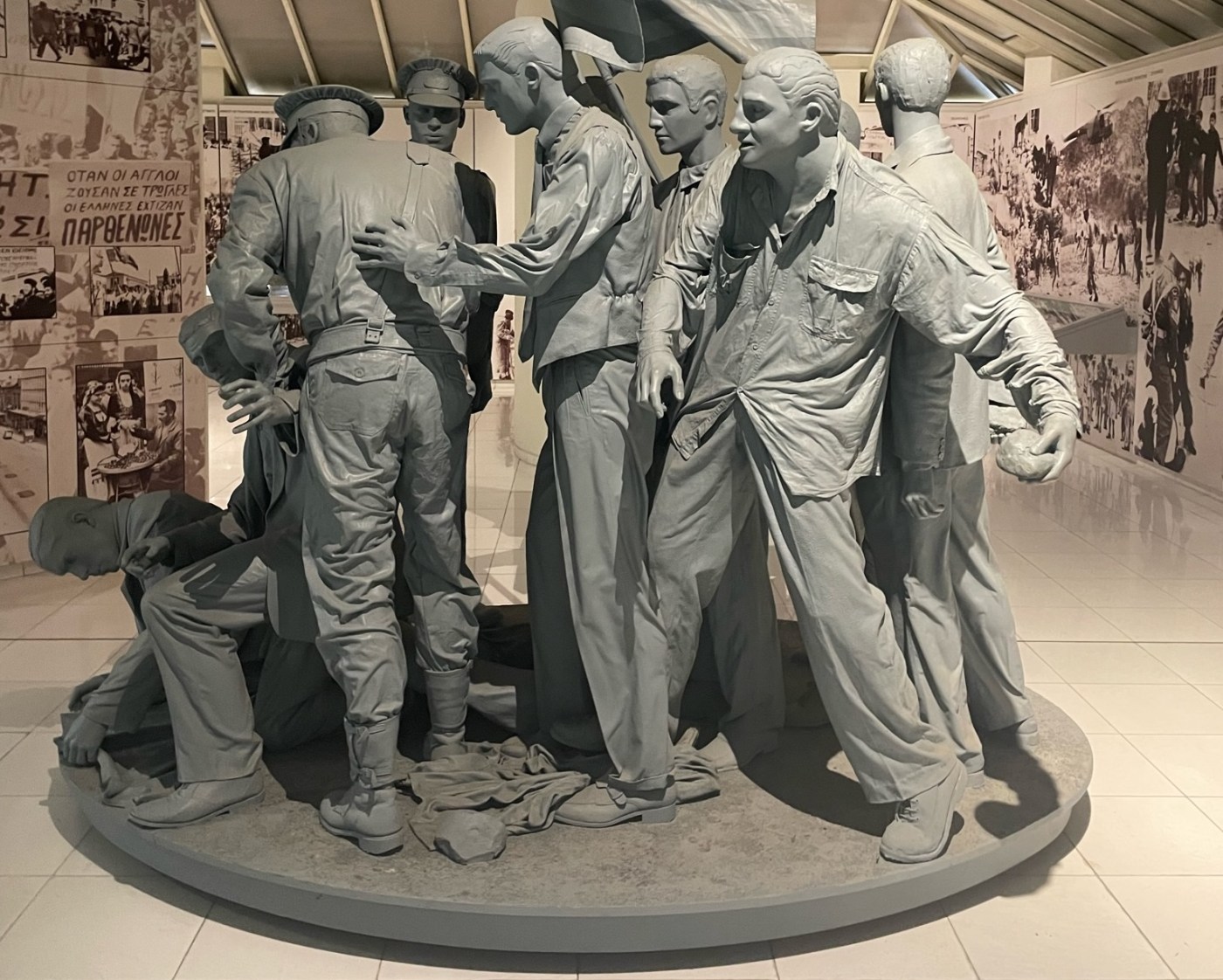

Personal artefacts such as clothing and diaries are also employed to generate emotional connections, helping visitors imagine the lives of those who fought. These items are powerful storytelling tools, immortalising EOKA and their efforts. In conclusion, the GMNS in Nicosia offers a deeply personal exploration of the Cyprus Problem. Its focus on the EOKA movement and the struggle against the British provides key insights into the roots of the conflict and the ongoing division between Greek and Turkish Cypriots. The museum’s approach helps visitors understand the emotional and social aspects of the conflict, showing how collective memory and identity shape Greek Cypriots’ views. Our research added to Papadakis’, confirming that the National Struggle Museum used effective use of language and structure to emotively retell their history. He similarly criticised their construction of imagined communities and their subsequent creation of collective memories, possibly impacting the visitors’ perceptions of the “other” side. These collective memories, such as graphic images of dead Greek Cypriots often without context, have the potential to further divide the communities.

Madeline and Beth were visiting Cyprus as part of a Newcastle University undergraduate-level geography module taught by Professor Nick Megoran, Dr Craig Jones, Dr Matt Benwell and Dr Ingrid Medby. To find out more about this course, please read their blogpost.

Further Reading

A. T. Hollander, “The Heromartyrs of Cyprus: National Museums as Greek Orthodox Hagiographical Media”, Material Religion 16.2 (2020): 131–161.

Y. Papadakis, “The National Struggle Museums of a Divided City”, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 17.3 (1994): 400–419.

T. Stylianou-Lambert and A. Bounia, The Political Museum. (London: Routledge, 2016).

Blogposts are published by TLP for the purpose of encouraging informed debate on the legacies of the events surrounding the Lausanne Conference. The views expressed by participants do not necessarily represent the views or opinions of TLP, its partners, convenors or members.